C ULTURE N AME

ItalianA LTERNATIVE N AMES

Republic of Italy, Italia, Repubblica ItalianaO RIENTATION

Identification. The Romans used the name Italia to refer to the Italian peninsula. Additionally, Italy has been invaded and settled by many different peoples. Etruscans in Tuscany preceded the Romans and Umbria, while Greeks settled the south. Jews entered the country during the period of the Roman republic, and Germanic tribes came after the fall of Rome. Mediterranean peoples (Greeks, North Africans, and Phoenicians) entered the south. The Byzantine Empire ruled the southern part of the peninsula for five hundred years, into the ninth century. Sicily had many invaders, including Saracens, Normans, and Aragonese. In 1720, Austrians ruled Sicily and at about the same time controlled northern Italy. There is a continuing ethnic mixing.Location and Geography. Italy is in south central Europe. It consists of a peninsula shaped like a high–heeled boot and several islands, encompassing 116,300 square miles (301,200 square kilometers). The most important of the islands are Sicily in the south and Sardinia in the northwest. The Mediterranean Sea is to the south, and the Alps to the north. A chain of mountains, the Apennines, juts down the center of the peninsula. The fertile Po valley is in the north. It accounts for 21 percent of the total area; 40 percent of Italy's area, in contrast, is hilly and 39 percent is mountainous. The climate is generally a temperate Mediterranean one with variations caused by the mountainous and hilly areas.

Italy's hilly terrain has led to the creation of numerous independent states. Moreover, agriculture in most of the country has been of a subsistence type and has led to deforestation. Since World War II, many Italians have turned away from rural occupations to engage in the industrial economy.

Rome was a natural choice for the national capital in 1871 when the modern state was united after the annexation of the Papal States. Rome recalls Italy's former grandeur and unity under Roman rule and its position as the center of the Catholic Church.

Demography. Italy's population was approximately 57 million in 1998. The population growth rate is .08 percent with a death rate of 10.18 per 1,000 and a birthrate of 9.13 per 1,000. Life expectancy at birth is 78.38 years. Population growth declined quickly after World War II with the industrialization of the country.

The majority of the people are ethnically Italian, but there are other ethnic groups in the population, including French–Italians and Slovene–Italians in the north and Albanian–Italian and Greek–Italians in the south. This ethnic presence is reflected in the languages spoken: German is predominant in the Trentino–Alto Adige region, French is spoken in the Valle d'Aosta region, and Slovene is spoken in the Trieste–Gorizia area.

Linguistic Affiliation. The official language is Italian. Various "dialects" are spoken, but Italian is taught in school and used in government. Sicilian is a language with Greek, Arabic, Latin, Italian, Norman French, and other influences and generally is not understood by Italian speakers. There are pockets of German, Slovene, French, and other speakers.

Symbolism. Italian patriotism is largely a matter of convenience. Old loyalties to hometown have persisted and the nation is still mainly a "geographic expression" (i.e., there is more identity with one's home region than to the country as a

Italy

H ISTORY AND E THNIC R ELATIONS

Emergence of the Nation. It was not until the middle of the nineteenth century that Italy as we know it today came to be. Until that time, various city-states occupied the peninsula, each operating as a separate kingdom or republic.Forces for Italian unification began to come together with the rise of Victor Emmanuel to the throne of Sardinia in 1859. That year, after the French helped defeat the Austrians, who had come to rule regions through the Habsburg Empire, Victor Emmanuel's prime minister, Count de Cavour of Sardinia, persuaded the rest of Italy except the Papal States to join a united Italy under the leadership of Victor Emmanuel in 1859. In 1870 Cavour managed to be on the right side when Prussia defeated France and Napoleon III, the Pope's protector, in the Franco-Prussian War. On 17 March 1861, Victor Emmanuel of Sardinia was crowned as king of Italy. Rome became the capital of the new nation.

Italy's history is long and great. The Etruscans were the first major power in the Italian peninsula and Italy was first united politically under the Romans in 90 B.C.E. After the collapse of the Roman Empire in the fifth century C.E. , Italy became merely a "geographic expression" for many centuries. Chaos followed the fall of the Roman Empire. Charlemagne restored order and centralized government to northern and central Italy in the eight and ninth centuries. Charlemagne brought Frankish culture to Italy, and under the Franks, the Church of Rome gained much political influence. The popes were given a great deal of autonomy and were left with control over the legal and administrative system of Rome, including defense.

The Carolingian line became increasingly weak and civil wars broke out, weakening law and order. Arabs invaded the mainland from their strongholds in Sicily and North Africa. In the south, the Lombards claimed sovereignty, where they established a separate government, until they were replaced by the Normans in the eleventh century.

City governments, however, had profited from Carolignian rule and remained vibrant centers of culture. Local families strengthened their hold on the rural areas and replaced Carolingian rulers. Italy had become difficult to rule from a central location. It had become a collection of city–states.

Through the ensuing years, numerous rulers from beyond the Alps, with or without the consent of the papacy, failed to impose their authority. Throughout the fourteen and fifteenth centuries of campanilismo (local patriotism), only a minority of people would have heard the word "Italia." Loyalties were predominantly provincial. However, there were elements that made a strong contrast to the world beyond the Alps: a common legal culture, high levels of lay education and urban literacy, a close relationship between town and country, and a nobility who frequently engaged in trade.

Three features in particular from this period solidified the notion of a unified culture. The first was the maturing of the economic development that had originated in the earlier centuries. Northern and central Italian trade, manufacture, and financial capitalism, together with increasing urbanization, were to continue with extraordinary vigor and to have remarkable influence throughout much of the Mediterranean world and Europe as a whole—a development that served as the necessary preliminary for the expansion of Europe beyond its ancient bounds at the end of the fifteenth century. Second came the extension of de facto independent city–states, which, whether as republics or as powers ruled by one person or family, created a powerful impression upon contemporaries and posterity. Finally, and allied to both these movements, it was from this society that was born the civilization of the "Italian Renaissance" that in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries was to be exported to the rest of Europe.

Italian rivalries of status, class, family, and hometown prevented unity throughout its history. The period from the fifteenth through the mid-eighteenth centuries was no exception. Nations grew and their ambitions, as well as those of the Italian city–states, continued to plague Italy. France and Spain in particular intervened in Italian affairs. Moreover, the chaos caused by these invasions led the Italian states to seek to further their own particular goals.

Italy became part of the Spanish Habsburg inheritance in 1527 when the Spanish king Charles I (Holy Roman Emperor Charles V) sent his troops in to take over Rome. Spain established complete control over all the Italian states except Venice.

Italy was ready for the new ideas of the French Enlightenment after the economic depression, plagues, wars, famines, and invasions of the seventeenth century. Italian intellectuals resented the supranational character of the papacy, the immunities of clerics from the state's legal and fiscal apparatus, the church's intolerance and intransigence in theological and institutional matters, and its wealth and property, and demanded reforms. Some changes in administration, taxation, and the economy were made by Habsburg rulers Maria Theresa and Joseph, but these reforms did not go far enough. The French Revolution and Napoleon's army demonstrated that a united Italy was possible and that arms might be the only way to achieve it.

Under the leadership of Victor Emmanuel, Count de Cavour, and Giuseppe Garibaldi, the various city-states moved toward unity. The writings of Allessandro Manzoni in the common tongue aided the forging of an Italian identity. His I Promessi

A man in elaborate costume at an outside café celebrates during the Venice Carnival in Piazza San Marco, Venice.

Ethnic Relations. Many countries and peoples have occupied Italy over the centuries. Italians resented each of these conquerors. However, they intermarried with them and accepted a number of their customs. Many customs, for example, in Sicily are Spanish in origin.

Italians have assimilated a number of people within their culture. Albanians, French, Austrians, Greeks, Arabs, and now Africans have generally found a welcome in peaceful social interaction. This mixture is reflected in the wide variety of physical characteristics of the people—skin and hair colorings, size, and even temperaments. Italians easily incorporate new foods and customs into the national mix. In all, there are about one million resident foreigners.

U RBANISM , A RCHITECTURE, AND THE U SE OF S PACE

The northern area is highly industrialized and urbanized. Milan, Turin, and Genoa form the "industrial triangle." After World War II, there was a great migration to urban areas and into industrial occupations.In spite of the previous agricultural and rural nature of Italy's Mezzogiorno (south), architecture there as well as in more industrialized areas of Italy has followed urban models. The architecture throughout Italy has strong Roman influences. In Sicily, Greek and Arabic ones join these influences. Throughout, a strong humanistic tone prevails but it is a humanism touched with deep religious feeling. There is a "family" feeling about the divine that often baffles non–Italians.

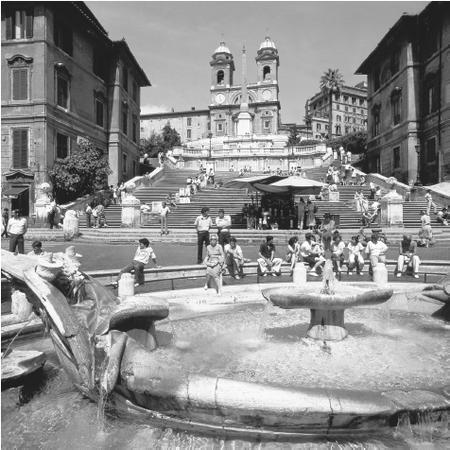

Italians tend to cluster in groups, and their architecture encourages this clustering. The piazzas of each town or village are famous for the parading of people through them at night with friends and relatives. Public space is meant to be used by the people, and their enjoyment is taken for granted.

F OOD AND E CONOMY

Food in Daily Life. Food is a means for establishing and maintaining ties among family and friends. No one who enters an Italian home should fail to receive an offering of food and drink. Typically, breakfast consists of a hard roll, butter, strong coffee, and fruit or juice. Traditionally, a large lunch made up the noon meal. Pasta was generally part of the meal in all regions, along with soup, bread, and perhaps meat or fish. Dinner consisted of leftovers. In more recent times, the family may use the later meal as a family meal. The custom of the siesta is changing, and a heavy lunch may no longer be practical.There are regional differences in what is eaten and how food is prepared. In general, more veal is found in the north, where meals tend to be lighter. Southern cooking has the reputation of being heavier and more substantial than northern cooking.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. There are special foods for various occasions. There is a special Saint Joseph's bread, Easter bread with hard–boiled eggs, Saint Lucy's "eyes" for her feast day, and the Feast of the Seven Fishes for New Year's Eve. Wine is served with meals routinely.

Basic Economy. Only about 4 percent of the gross national product comes from agriculture. Wheat, vegetables, fruit, olives, and grapes are grown in sufficient quantities to feed the population. Meat and dairy products, however, are imported.

Lombardy is, perhaps, the richest area of Italy. It is the location of the fertile Po river valley as well as Milan, the chief commercial, industrial, and financial center. It is also the major industrial area of Italy. Textiles, clothing, iron and steel, machinery, motor vehicles, chemicals, furniture, and wine are its major products. It stands in marked contrast to the southern area of the country that has only recently begun to emerge from its agricultural economy.

Italy began its major shift from agriculture to a major industrial economy after World War II. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, it is the fifth-largest economy in the world. Italy has only recently abandoned its interventionist economic policies that created periods of recession. Under pressure from the European Union it has begun to face its federal deficit, crime, and corruption. The state has begun a major retreat from participating in economic activities. Unemployment, however, has remained around 12 percent and economic growth has risen barely above the 1 percent level as the new millennium began.

Land Tenure and Property. Italy's economy is basically one of private enterprise. The government, however, owns a large share of major commercial and financial institutions. For example, the government has major shares in the petroleum, transportation, and telecommunication systems. In the 1990s Italy began to more away from government ownership of business.

Commercial Activities. Most of Italy's commercial centers are in the developed northern region. Milan is the most important economic center of Italy. It is located in the midst of rich farmland and great industrial development. It has extensive road and rail connections, aiding its industrial power. Milan is predominant in the production of automobiles, airplanes, motorcycles, major electric appliances, railroad materials, and other metalworking. It is also important for its textiles and fashion industry. Chemical production, medicinal products, dyes, soaps, and acids are also important. Additionally, Milan is noted for its graphic arts and publishing, food, wood, paper, and rubber products. It has kept pace with the world of electronics and cybernetic products.

Genoa remains Italy's major shipbuilding center. However, it also produces petroleum, textiles, iron and steel, locomotives, paper, sugar, cement, chemicals, fertilizers, and electrical, railway, and marine equipment. It is also a center for finance and commerce. Genoa is Italy's major port for both passengers and freight.

Florence, located about 145 miles (230 kilometers) northwest of Rome, is renowned for its magnificent past. Tourists flock to Florence to see its unparalleled art treasures. Turin, in contrast, is noted for automobile manufacturing and its modern pace of life. It is located just east of the Alps. In addition to Fiats and Lancias, Turin manufactures airplanes, ball-bearings, rubber, paper, leather-work, metallurgical, chemical, and plastic products, and chocolates and wines.

Major Industries. Italy is important in textile production, clothing and fashion, chemicals, cars, iron

Boats float in a canal lined by houses in Venice.

Division of Labor. There is a great hierarchy of prestige according to one's occupation. Those in professional jobs have greater prestige than those in manual labor. The importance of tailoring one's lifestyle to the appropriate job is significant. Thus, anyone who works with a pencil and paper, or today a computer, is above others who get their hands dirty.

S OCIAL S TRATIFICATION

Classes and Castes. There is a vast difference in wealth between the north and the south. There are also the usual social classes that are found in industrial society. Italy has a high unemployment rate, and differences between rich and poor are noticeable. New immigrants stand out since they come from poorer countries. The government has had a vast social welfare network that has been cut in recent years to fit the requirements of the European Union. These budget cuts have fallen on the poorer strata of society.Symbols of Social Stratification. Speech is a social boundary marker in Italy. The more education and "breeding" a person has, the closer that person's speech comes to the national language and differs from a dialect. Style of dress, choice of food and recreation, and other boundary markers also prevail. Clothes from Armani, Versace, and other fashion designers are beyond the reach of the poor. There is a difference also in what food one eats, certain food being more prestigious, such as veal or steak, than others. Although pasta and bread are still staples for all classes, it is what else and in what quantity meat is available that marks social classes.

Leisure and the manner in which it is spent are also class boundary markers. The more leisure and the great the amount of travel mark off groups from each other. The more private the beaches, the longer the siesta, the more opulent the family villa, the greater the prestige. Soccer is for everyone, but more expensive entertainment is restricted by cost.

P OLITICAL L IFE

Government. Italy is a republic with twenty regions under the central government. In 1861, the Italian states were unified under a monarch. The republic was formed on 2 June 1946 and on 1 January 1948, the republic's constitution was proclaimed. There are three branches of government: executive, judicial, and legislative. The legal system is a combination of civil and ecclesiastical law. The system treats appeals as new trials. There is a Constitutional Court that has the power of judicial review. A chief of state (the president) and a head of government (the prime minister) head the executive branch. There have been numerous changes of government since the end of World War II. There are two houses in the parliament: the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies. Both houses have elected and appointed members chosen through a complicated system of proportional representation and appointed. Voters must be 25 years old to vote for senators but only 18 in all other elections.Leadership and Political Officials. Italy has been plagued with too many political parties and, in some sense, every Italian is his or her own political party. Recent reforms have not ended the problem. New parties have grown from combinations or alliances of a number of parties. The major parties are Olive Tree, Freedom Pole, Northern League, Communism Refoundation, Italian Social Movement, Pannella–Sgarbi's List, Italian Socialist, Autonomous List, and Southern Tyrol's List. The Olive Tree is the party of the democrat left. The Freedom Pole is the party of the right to center. Other parties occupy various positions on the political spectrum. There are certain rules of respect toward those in power. Presents are usually given, and support is promised in return. People approach those in power through intermediaries.

Social Problems and Control. Italians resent intrusions into private and family life. They have had centuries of practice in evading what they consider unjust laws. The major crime problem comes from the Mafia. Special courts and task forces have made some headway against the Mafia. Scandals linking politicians and judges to the Mafia have led to greater action in seeking its extermination. Street crime, such as robbery, is prevalent in the larger cities, and murder is a serious problem, with about one thousand five hundred per year, and an additional two thousand attempted murders per annum. The national police are found throughout the country. The judicial system operates on an inquisitorial system. There is no presumption of innocence, and judges routinely question defendants. The Catholic Church, family, and friends serve as strong informal social controls.

Military Activity. The country's president is the commander of the armed forces. He also chairs the Supreme Council of Defense. Male military service is compulsory. Italy is a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The first significant deployment of troops outside Italy took place in 1997, when troops were sent to Albania to help control the chaos that resulted with the collapse of the economy. As a member of NATO, the country allowed its air bases to be used in attack on Yugoslavia.

Italian architecture—especially the use of public space—encourages socializing.

S OCIAL W ELFARE AND C HANGE P ROGRAMS

Until the 1990s Italy had a cradle–to–grave social welfare system. Italy began to cut its involvement in these programs in response to pressure from its European partners to cut its budget deficits. These changes affected unemployment insurance, retirement pensions, child support, and other major programs. However, Italy's system is still impressive when compared with that of the United States.N ONGOVERNMENTAL O RGANIZATIONS AND O THER A SSOCIATIONS

The Catholic Church is deeply involved in various charitable activities in Italy. In addition to the Church's activities on behalf of the homeless, poor, orphans, prisoners, and others, there are a number of other NGOs operating in Italy. The Italian Red Cross and Caritas, for example, are involved in various projects to resettle refugees in Italy. The Association for Minority People works on behalf of minorities worldwide, including in Italy. COSPE is another agency that works with minorities and refugees, teaching languages to minority ethnic groups in Italy, and with programs in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe.G ENDER R OLES AND S TATUSES

Division of Labor by Gender. Traditionally, men went out to work and women took care of the home. After World War II, that arrangement changed rapidly. While old notions of gender segregation and male dominance prevail in some rural areas, Italian women have been famous for their independence and many anthropological and historical works point out that their assumed past subordination was often overstated. Currently, women participate in every aspect of political, economic, and social life. Women are equal under the law and attend universities and work in the labor force in numbers commensurate with their share of the population.A sign of female independence is Italy's negative population growth. It is true, however, that women continue to perform many of the same domestic tasks they did in the past while assuming new responsibilities.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. In Italian culture, men were given preferential status and treatment. Women were assigned the position of the "soul" of the family, while men were the "head." Men were to support and defend the family while women raised the children and kept themselves chaste so as not to disgrace the family. How much of the ideal was ever found in the real world is problematic. Women in general always had more power than they were traditionally supposed to have. Currently, Italian women are often considered the most liberated in Europe.

M ARRIAGE , F AMILY, AND K INSHIP

Marriage. In the past, marriages were arranged and women brought a dowry to the marriage. However, there were ways to help one's parents arrange marriage with the right person. The poorer classes, in fact, had more freedom to do so than did the wealthier ones. Dowries could be waived and often were. Currently, marriage is as free as anywhere else in the world. Except for those who enter the clergy, almost all Italians marry. But there is a custom in many families for a child to remain unmarried to care for aged parents. Divorce was forbidden until recently.Domestic Unit. The family is the basic household unit. It may vary in size through having other relatives live with the nuclear family or through taking in boarders. Often two or more nuclear families may live together. It is common for newly married couples to live for a time with the bride's parents. Traditionally the husband was the ruler of the family, in theory, while the wife took care of the day–to–day operations. The reality may have been quite different. Tasks have traditionally been assigned according to age and sex. There is evidence that there is some change in this system as more and more often both parents work outside the home.

Inheritance. By law, all members of the family inherit equally. Special personal items may be given to loved ones before death to assure their being received by the designated heir.

Kin Groups. Italians are famous for their family lives. They are often tied to one another by relationships on both sides of the family. They can and do expand or contract their extended kin groups by emphasizing or de-emphasizing various kinship ties. Usually, children of the same mother feel a necessity to cooperate against the outside world. Other ties may be egocentric. Generally, a male feels closest for many reasons to his mother's sisters and their kin. These kin traditionally protected him from the father's side, traditionally the side of "justice" as opposed to "mercy" and unmitigated love.

S OCIALIZATION

Infant Care. There is a fear that others will be jealous of a healthy and bright baby. Care is taken not to be foolish and boast too much about one's child. There are many charms and practices to ward off dangers, such as the evil eye. Children are coddled and held to keep them happy and content. They eat at will, are allowed to sleep with their parents, and are taken on family outings. Although times are changing it is still common to have families go to nightclubs and restaurants together. Parents are glad to see signs of activity in children and tease youngsters almost mercilessly to teach them to stand up for themselves. Older children routinely care for younger ones.Child Rearing and Education. Children are indulged when young. As they grow older, they are expected to obey their parents and contribute to the

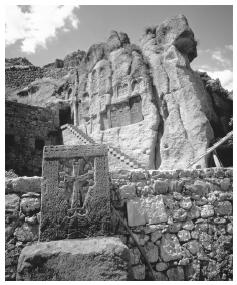

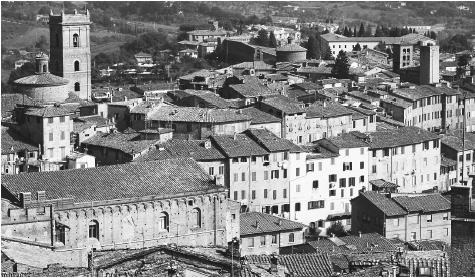

Tiled rooftops on brick buildings and homes in Siena. Architecture throughout Italy shows strong Roman influences.

E TIQUETTE

Italians generally are effusive in their public behavior. There is a great deal of public embracing and kissing upon greeting people. It is also polite to sit close to people and to interact by lightly touching people on the arms. Italian gazes are intense. It is felt that someone who cannot look you in the eyes is trying to hide something. Elders expect and get respect. They enter a room first. Men stand for women and youngsters for adults. Children tend to be used to run errands and help any adult, certainly any adult in the family. Gazing intently at strangers is common, and Italians expect to be looked at in public. Traditionally, younger women deferred to men in public and did not contradict them. Older women, however, joined in the general give and take of conversation without fear. Italians have little respect for lines and generally push their way to the front. There is great care given to preserving one's bella figura, dignity. Violating another's sense of self–importance is a dangerous activity.R ELIGION

Religious Beliefs. Ninety percent of the population is Roman Catholic. The other 2 percent is mainly comprised of Jews, along with some Muslims and Orthodox and Eastern Rite Catholics. The general supernatural beliefs are those of the Catholic Church as mixed with some older beliefs stretching back to antiquity. In Sicily, for example, Arabic and Greek influences have mixed with popular Spanish beliefs and been incorporated into Catholicism.

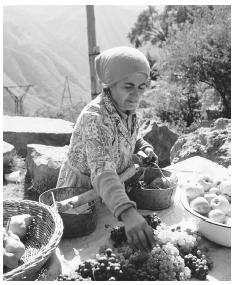

A woman purchases produce at the Campo de Fiori Market in Rome.

Rituals and Holy Places. Italy is filled with over 2000 years' worth of holy places. Rome and the Vatican City alone have thousands of shrines, relics, and churches. There are relics of Saint Peter and other popes. Various relics of many saints, places holy to Saint Francis of Assisi, shrines, places where the Virgin Mary is reputed to have appeared, and sites of numerous miracles are found across the country. Similarly, religious ceremonies are frequent. There are the usual holy days of the Roman Catholic Church—Christmas, Easter, Pentecost, the Immaculate Conception and others. In addition, there are local saints and appearances by the Pope. The sanctification of new saints, various blessings, personal, family, and regional feast days and daily and weekly masses add to the mix. There are also various novenas, rosary rituals, sodalities, men's and women's clubs, and other religious or quasi–religious activities.

Death and the Afterlife. Italians generally believe in a life after death in which the good are rewarded and the evil punished. There is a belief in a place where sins are purged, purgatory. Heaven and hell are realities for most Italians. The deceased are to be remembered and are often spoken to quietly. Funerals today take place in funeral parlors. Respect for the dead is expected. Failure to attend a wake for a family member or friend is cause for a breach of relationship unless there is a patently valid reason.

M EDICINE AND H EALTH C ARE

Italy was a pioneer in modern health care with its medieval centers for medical study. Although modern Italy has a number of modern doctors and health specialists, it has had a history of healers and potion–makers. There was a prevalent belief, for example, in people having "healing hands." These people, it was felt, could heal soreness and broken bones by touch and manipulation. Others could cause disease through incantations or spells. Various faith healers practiced their arts.S ECULAR C ELEBRATIONS

Most secular celebrations also are tied to religious holidays, like Christmas or New Year's (the Circumcision of Jesus). These celebrations tend to be family affairs. The Anniversary of the Republic is celebrated on 2 June. There is a show of patriotism through air shows and fireworks. Generally, it, too, is a day off and a family holiday. Independence Day is March 17 and provides another opportunity for family activity.T HE A RTS AND H UMANITIES

Support for the Arts. Italian art has a long history. Part of that history is the support it has received from public and private benefactors. That tradition continues into the present day with numerous benefactors who support the arts and humanities. These include the Agnelli Foundation, La FIMA (Foundazione Italiana per la Musica Antica), and numerous others.Literature. Italian literature has its roots in Roman and Greek literature. Until about the thirteenth century Italian literature was written in Latin. There were various poems, legends, saint's lives, chronicles and similar literature. French and Provencal was also used. This literature concerned Charlemagne and King Arthur.

In the thirteenth century Sicilians composed the earliest poetry written in Italian at the court of Frederick II. Frederick and his son Manfred administered the Holy Roman Empire from Sicily. This poetry was a courtly poetry, following the Provencal models closely. When the Hohenstaufen dynasty fell in 1254, the capital of Italian poetry moved north. There were poets before Dante, especially Guittone d'Arezzo and Guido Guinizelli, the founder of the dolce stil nuovo —sweet new style. Dante's La Vita Nuova (1292) is in this style, and it influenced Petrach and other Renaissance writers. At about the same time as the dolce stil nuovo appeared, Saint Francis of Assisi began another type of poetry, a devotional style filled with love for all of God's creatures. Dante's greatest work was La Divine Comida.

Petrarch was the next great literary figure in Italy. He worked to restore classical Latin as the language of scholarship and literature. Petrarch believed that Italy was the heir of Rome, and he worked to foster Italian nationalism and unity. In spite of his classical scholarship, his work in Italian is Petrarch's greatest contribution to literature. His sonnets to Laura bring a fiery passion to Italian literature. Boccaccio's Decameron (1353) drew on both Dante and Petrarch as influences and in turn influenced numerous writers. It not only uses the vernacular but also uses true–to–life stories.

The fifteenth century was the period of the High Renaissance and included "universal men" such as Michelangelo, Leon Battista Alberti, and Leonardo da Vinci, among others. These men generally profited from patrons of the arts such as Lorenzo de'Medici and the Popes, such as Alexander VI. The first major Italian drama was Orfeo (c. 1480) written by Angelo Poliziano. There were still works done in the medieval geste style, which were based on the medieval romances.

In the sixteenth century, Italian rose to great heights with the writing of Pietro Bembo, Nicolo Machiavelli, and Ariosto. Machiavelli is best known for The Prince (1640), the first realistic work of political science and a call for Italian unity. Ariosto's poem, Orlando furioso (1516) is an epic dealing with Charlemagne, an old theme but with a new sophistication. There were numerous fine works written during century. The early exuberance was stifled, however, by the mood of the Counter–Reformation. Nonetheless, Torquato Tasso's masterpiece, Geusalemme liberata (1575), managed to break through the fog of repression. However, it received such petty criticism that Tasso wrote a poor new version of the poem.

The seventeenth and eighteenth century saw a decline in the standard of living in Italy. Trade had shifted to the Atlantic and Italy was under the political domination of Spain, France, and Austria. It was also the period of the baroque. The one great work of the period is Giambattista Marino's Adone (1623). The majority of other work in the century is depressingly gloomy, as befits the general tenor of Italian life of the period.

The next century saw a movement toward simplicity, the Arcadia movement. It was a period of naivete in style and simplicity in narrative. Greek models were used. The period was also influenced by the French Enlightenment.

The nineteenth century was the century of the Risorgimento. Giacomo Leopardi wrote magnificent lyric poems. Leopardi shows great feeling in his works as well as a deep nationalism. Alessandro Manzoni's I promessi sposi (1825–1827) is a great work of nationalistic fiction. Manzoni called for a

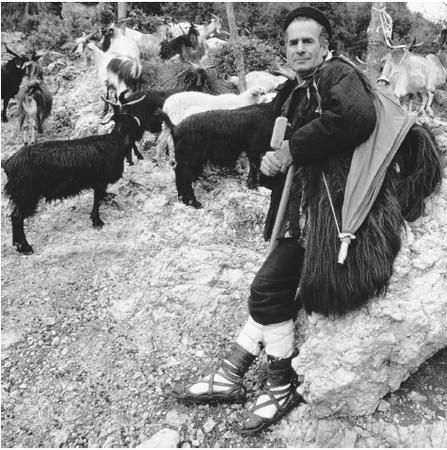

A mountain shepherd with goats in Lenola, circa 1985. After World War II, Italy began moving from an agricultural economy to an industrial economy.

After World War II Italian literature blossomed again. All the major movements found in the West had their counterparts in Italy. A simple listing of major figures is sufficient to suggest the importance of modern Italian literature. In poetry, there are Giuseppe Ungaretti, Eugenio Montale, and Salvatore

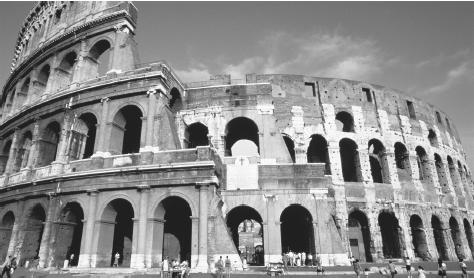

The Coliseum in Rome, a popular tourist spot.

Italy has a cultural heritage that is felt everywhere in the country. Remains of Greek and Etruscan material culture are found throughout the south and middle of the peninsula. Roman antiquities are found everywhere. Pompeii and Herculaneum are famous for their well–preserved archeological remains. The city of Rome is itself a living museum. Throughout the country there are churches, palaces, and museums that preserve the past. There are, for example, over 35 million art pieces in its museums. Moreover, Italy has 700 cultural institutes, over 300 theaters, and about 6,000 libraries, which hold over 100 million books.

Italy's museums are world famous and contain, perhaps, the most important collections of artifacts from ancient civilizations. Taranto's museum, for example, offers material enabling scholars to probe deeply into the history of Magna Gracie. The archaeological collections in the Roman National Museum in Rome and in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples are probably among the world's best. Similarly, the Etruscan collection in the National Archaeological Museum of Umbria in Perugia, the classical sculptures in the Capitalize Museum (Museo Capitolino) in Rome, and the Egyptian collection in the Egyptian Museum in Turin are, perhaps, the best such collections in the world.

The classical age is not the only age represented in Italy's museums. The Italian Renaissance is well represented in a number of museums: the Uffizi Gallery (Galleria degli Uffizi), Bargello Museum (Museo Nazionale del Bargello), and Pitti Palace Gallery (Galleria di Palazzo Pitti, or Galleria Palatina) are all located in Florence.

The Uffizi contains masterpieces by Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Botticelli, Piero della Francesca, Giovanni Bellini, and Titian. The Bargello has specialized in Florentine sculpture, with works by Michelangelo, Benvenuto Cellini, Donatello, and the Della Robbia family. The Pitti Palace has a fine collection of paintings by Raphael, as well as about five hundred important works of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, which were collected by the Medici and Lorraine families.

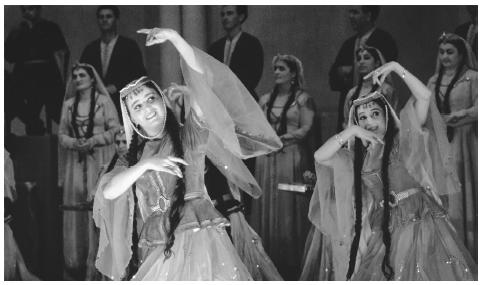

Performance Arts. Italian music has been one of the major glories of European art. It includes the Gregorian chant, the troubadour song, the madrigal, and the work of Giovanni Palestrina and Claudio Giovanni Monteverdi. Later composers include Antonio Vivaldi, Alessandro and Domenico Scarlatti, Gioacchino Rossini, Gaetano Donizetti, Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini, and Vincenzo Bellini. The most famous of Italy's opera houses is La Scala in Milan. There are other famous venues for opera, including San Carlo in Naples, La Fenice Theatre in Venice, and the Roman arena in Verona. Additionally, there are fifteen publically-owned theaters and numerous privately-run ones in Italy. These theaters promote Italian and European plays as well as ballets.